How to build a sound security system in your CodeVille?

A brief introduction to basic concepts in mutation testing.

We all use different kinds of software in our daily life: using Skype to call our families, using Microsoft Word to write articles, using Facebook to share our lives. However, software can also go wrong if developed in a careless way. For example, when you call your family via Skype, it suddenly goes to your boss. What a disaster? Today, we are going to learn how software engineers test their code.

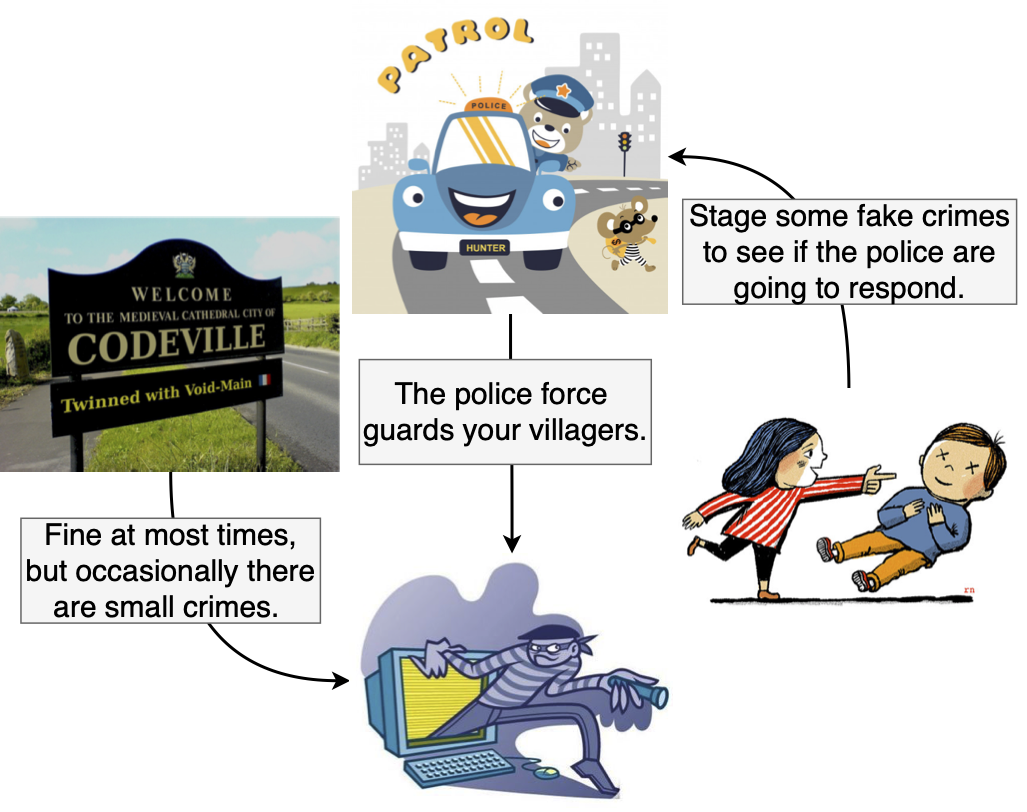

Before we look into how software testing works, let us start with a story: Imagine you are a software engineer or programmer. Your daily work is to program and write code. One day, your code becomes a small town, called CodeVille. Your small town is fine at most times, but occasionally there are small crimes caused by some naughty villagers (the error-prone statement in your code). We call these crimes bugs. To deal with these annoying crimes in the village, we usually block the scene of the crime and clean up the villagers. Maybe we also try to punish the villagers to prevent the situation happens again. That procedure is exactly the debugging routine: first of all, target where the bugs are and then clean up these bugs. Afterwards, we also try to stop these situations happening again by adding error handlers. But cleaning up after the crime is not an ideal strategy. It is better to catch the crime early before real damage is done.

Unit Testing

How to act quickly enough to prevent actual damages? In reality, our government would hire a branch of police officers to make sure we citizens are law-abiding. So in your virtual town, CodeVille, unit testing is also acting as a kind of police force to guard your villagers. To put in a simple way, unit testing is the smallest testable part of your code, like functions, classes, or procedures. Its goal is to make sure each part of your code is working correctly. So now can you say CodeVille is safe enough to catch every single crime by employing unit test as a safeguard? Similar questions also arise in real software testing: how do you know if your tests are any good? A possible way to know how good your tests are is to write tests for your tests. What? Are you kidding? Tests for tests, then tests for tests of tests, then tests for tests of tests of tests … this method will never stop.

Test Coverage

We do want some reassurance that the police force is actually doing their jobs. Of course, we do not want to adopt that endless tests-for-tests strategy. If you have some experience of testing before, you probably come up with the term “Test Coverage”. Test coverage measures the percentage of your code has been exercised by a set of test. Back to your CodeVille, you are beginning to check whether your police force was patrolling all the parts of the town. This strategy seems quite helpful; you now know some parts of your town are the dangerous zone which has never been patrolled by the police. You can assign additional police officers to go to that area, in another word, you can write more unit tests to cover that statement. But somehow you still have some worries about if your police officers are taking their jobs seriously: are they paying much attention to every block they pass? Or are they only interested in the doughnuts and coffee at hands while patrolling the street?

Mutation testing

Can we do any better? Yes, we do! We can stage some fake crimes to see if the police are going to respond. That is exactly what mutation testing does. It injects tiny fake bugs called mutants into your code and looks for test failure. For example, mutation testing will change a subtraction to addition in your code, or swap ‘if’ statement to cause different logic relationship. Luckily, you do not need to get your feet wet by changing every single statement in your code: there are a variety of automated tools available for performing mutation testing in your code, like Pitest, MuJava. You just need to click a few buttons, and the tool will do the rest for you. You just need to be very patient to get the results: the repeated procedures of injecting artificial bugs and running the tests are extremely time-consuming. So now maybe you are wondering how to reduce the time of mutation testing. Many efforts have been put to solve this problem. For example, it seems unnecessary to stage all kinds of fake crimes to your police. You only perform this approach occasionally, like once a week or once a month (mutant sampling). Or you can rearrange your police force by their performance to catch the fake crimes as soon as possible (test prioritisation).

Beyond software testing

The story of the CodeVille almost ends up here. You probably get to know what is unit testing, why test coverage is necessary and how mutation testing works. No matter how much programming experience you have before, from now on, do some testing before or after you write down some code. You will certainly benefit a lot from forming the habit of testing in your programming routine.

“Testing shows the presence, not the absence of bugs.”

Also, bear in mind the famous quote from the Dutch computer pioneer Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. Testing does not show how good your code is, in another word, although you have achieved 100% test coverage, your code still has a chance to have bugs. So do not overestimate the role of testing! To make your programming time more enjoyable, simplicity is the golden rule.

Together with “unit testing”, “test coverage” and “mutation testing”, you can build a very sound security system for your village: it can take care of every corner of the town, and at the same time it also responds to fake crimes. But still keep an eye on your small town: it still has a chance to commit a crime now and then.

Thanks for Chris Rimmer to create the nice storyline of CodeVille, which inspired me to write down this blog.